The Equality of Men and Women

St. James Methodist Church 1889. Now St. James United Church. On September 5, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at this church about a few of the principles of Bahá’u’lláh, among them the equality of men and women, saying that the completeness and perfection of the human world are dependent upon the equal development of man and woman.

Generally, all human societies have evolved in similar patterns of development, leading to the family, the tribe, the city-state and the modern state. We do not have much information about early societies, as they rarely left written records about their way of life, especially with regard to the social status of women. Nevertheless, we know that raiding between tribes was frequent and practically represented the social norm. The capture of women was one motive for these tribal attacks in the wilderness. In cities and towns, the acquisition of women took on many nuances and forms within a general concept of exchange and sale. In the midst of this primitive and savage way of life, the Code of Hammurabi, which around 1790 B.C. provided for some protection of women in Babylonian society while preserving the superiority of men, may be seen as a big step forward in the long path towards a civilized relationship between men and women.

After the Babylonian civilization, there appeared the chain of Abrahamic religions, each of which gradually improved woman’s social position and offered better protection of her rights, but without putting in question men’s superiority. Gradually, religion reduced the restrictions imposed on women and improved their conditions within the limits of the prevailing conditions of life without disturbing the social equilibrium.

Genesis mentions a story of Eve’s disobedience under the influence of a serpent for which she is punished by labour pain and submission to man:

“Unto the woman He said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.”1

Further among the teachings of the Old Testament, we read: “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour’s.”2

In addition, women are exempt from certain rituals: “Three times in the year all thy males shall appear before the Lord GOD.”3

In the New Testament, the texts again indicate a distinction made with regard to women:

“For a man indeed ought not to cover his head, forasmuch as he is the image and glory of God: but the woman is the glory of the man. For the man is not of the woman; but the woman of the man. Neither was the man created for the woman; but the woman for the man.”4

Women were allowed participation in all religious prayers, and were given protection from polygamy and from sudden unjustified divorce. However, they remained under man’s authority:

“Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church…”5

“Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection. But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. For Adam was first formed, then Eve. And Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression.”6

Islam made polygamy conditional on just treatment, and gave women a share in inheritance and the right to subsidy in case of divorce, but maintained man’s authority over her:

“Men are superior to women on account of the qualities with which God hath gifted the one above the other, and on account of the outlay they make from their substance for them. Virtuous women are obedient, careful, during the husband’s absence, because God hath of them been careful. But chide those for whose refractoriness ye have cause to fear; remove them into beds apart, and scourge them: but if they are obedient to you, then seek not occasion against them: Verily God is High, Great.”7

The subordinate status of women in Islam seems likewise to be affirmed in the qur’ánic verse stating: “but the men are a step above them” (i.e. the women).8

It should be noted that these restrictions on women cannot be compared to the harshness of the pagan societies of the past or the dark ages. Studies of the ancient Greek tribes and cities indicate a discrimination and ruthlessness against women worse than the conditions among the women under the Arab Bedouin tribal system prevailing before Islam.

Women’s situation thus changed in accordance with the progress or deterioration of conditions of life, the concept of justice and the development of a social conscience. Their progress depended on the extent of education they were allowed to acquire.

A noteworthy example is the advancement in the education of women wherever reading was promulgated and books or magazines were made available to the ordinary people.

These slow progressive changes continued until the sudden important transformation brought about in the 19th century, which created new world conditions and new social and economic realities. A swift and important change affected the status of women: Women acquired financial independence, the right to elect and be elected in public national institutions, with however significant differences between western and eastern societies.

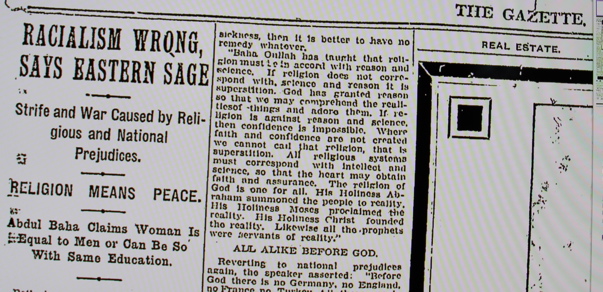

In another talk (reported in the Montreal Gazette), 'Abdu'l-Bahá said that the differences that exist at the present time are due only to the various degrees of education because women have not had the same opportunity as men.

Despite all these developments the right of women to equality remained as a dream until Abdu’l-Bahá raised the call for equality to a higher level: “Today questions of the utmost importance are facing humanity,” said ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “questions peculiar to this radiant century. In former centuries there was not even mention of them. Inasmuch as this is the century of illumination, the century of humanity, the century of divine bestowals, these questions are being presented for the expression of public opinion, and in all the countries of the world, discussion is taking place looking to their solution.

“One of these questions concerns the rights of woman and her equality with man. In past ages it was held that woman and man were not equal—that is to say, woman was considered inferior to man, even from the standpoint of her anatomy and creation. She was considered especially inferior in intelligence, and the idea prevailed universally that it was not allowable for her to step into the arena of important affairs. In some countries man went so far as to believe and teach that woman belonged to a sphere lower than human. But in this century, which is the century of light and the revelation of mysteries, God is proving to the satisfaction of humanity that all this is ignorance and error; nay, rather, it is well established that mankind and womankind as parts of composite humanity are coequal and that no difference in estimate is allowable, for all are human. The conditions in past centuries were due to woman’s lack of opportunity. She was denied the right and privilege of education and left in her undeveloped state. Naturally, she could not and did not advance. In reality, God has created all mankind, and in the estimation of God there is no distinction as to male and female.”9

In the West, after suffering the casualties and destruction of two world wars, political leaders in a number of countries discovered the importance of moral and spiritual principles in the development of a social conscience and, consequently, in reducing violence and altering the tradition of regarding war as solution for international differences. International attention to this fact led the world to integrate the protection of human rights into the rule of international law. Among these laws are women rights and their protection against discrimination.

The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted, on 18 December 1979, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and this Convention acquired force of international law on 3 September 1981. “By accepting the Convention, States commit themselves to undertake a series of measures to end discrimination against women in all forms, including:

• to incorporate the principle of equality of men and women in their legal system, abolish all discriminatory laws and adopt appropriate ones prohibiting discrimination against women;

The said Convention defined discrimination as being “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”

The power of women’s movements increased after women acquired equal political rights, the spread of girls’ education and women’s demonstrated ability to become, intellectually and financially, independent. Many of the freed women were inclined to separate their social status from their religious beliefs.

Despite the dispositions of this Covenant and other similar agreements, in the Eastern countries some of the statements issued or expressed from time to time in certain culturally conservative societies appear to ignore the principle of equality between men and women stipulated in the said Covenant. For example, some extremists express views that conceive the status of women and their social role in a manner greatly differing from the clauses of the Covenant. They declare the superiority of men to be a religious law and divine command, and consequently hold that the role of women should be limited to serving their families and looking after the children. They consider a working woman to have abandoned her femininity, rejected her role as wife and mother, and instead be pursuing her selfish ambitions in a struggle that is against men’s interests.

Such views have generated a strong reaction from human rights groups, as well as other groups concerned with the protection of women’s rights. To them, these are reactionary statements made for the purpose of perpetuating masculine control over women and tarnishing the image of working women, despite the fact that most of these women are providing financial assistance for their families. In addition, they note that working women are fulfilling their share in advancing their societies.

There are also more moderate voices that are attempting to establish the equality between men and women on the grounds of various religious concepts from the past. Referring to the story of Adam and Eve’s creation, they claim that religion has established the principle of the equality of all human beings because all were created from the same stock. These views, founded on antiquated religious concepts, do not seem to be very convincing, nor are they sufficiently strong to provide a platform for equality.

Nevertheless, assuming the story of creation has established equality in the creation of Adam and Eve, the scriptures of the same religions have explicitly and clearly discriminated between men and women. In addition, the story itself contradicts scientific evidence about the process of creation, which puts in question the dates and the other details of the story. As a result, individuals who investigate the truth and stipulate that their belief must be in accord with both science and religion reject this argument altogether. The story is a metaphor which no doubt has a deeper spiritual meaning than the naïve literal interpretation given to it so far.

Moreover, religious teaching makes men responsible for the discipline of their wives and permits them to resort to physical force, if need be, in order to insure a woman’s compliance with her husband’s directives. Such a teaching that legitimizes family violence and permits women’s humiliation is no longer practical or acceptable in present day society.

Family is the basic social unit for building a healthy modern society. The foundation of family relations should be love, not violence—on solving conflicts through consultation and the desire for cooperation. The time for authoritative leadership is over, whether within or outside the family.

Although the change affecting these obsolescent societies is a recent phenomenon, it is real. It is futile to deny the existence of a new consciousness. Without a doubt these forces of change will continue their penetration into deeper social strata until they reach the hearts and minds of people, and thereby eliminate the vain imaginings of the past.

Surprisingly, the concerted efforts of so many civil societies and international organizations since World War II, often under the auspices of the United Nations, have not yielded the expected results insofar as the equality of men and women is concerned.

This fact indicates the limits of human effort alone to overcome the traditional concepts and ideologies concerning the role of woman and her place in society. Unless and until a way is found for spiritual principles to change the old attitudes of men and women alike, the social transformation will be very slow with many setbacks.

In His talk delivered at the Unitarian Church in Philadelphia on 9 June 1912 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated: “In proclaiming the oneness of mankind He [Bahá’u’lláh] taught that men and women are equal in the sight of God and that there is no distinction to be made between them.”11 He dealt with this same question in His talk given at the Church of Messiah in Montreal on 1st September 1912, adding: “Bahá’u’lláh proclaimed the equality of the sexes, because women were not free. Men and women belong to the human race and are the servants of the same God. Before God there is no difference of gender. Whosoever has a purer heart and performs a better deed is nearer to God, irrespective of sex. The differences that exist at the present time are due only to the various degrees of education because women have not had the same opportunity as men. If women were given the same education, they would become equal in all degrees because both are human beings and share the same faculties and in this God has created no differences.”12

In my understanding this means that the equality of men and women is not a matter of acquisition, i.e. a notion that we learned as we progressed in civilization. Rather it is an inherent right stemming from their both being human, endowed with the same attributes and created from the same substance. The fact that this equality was not expressed was because of the conditions of society and the structures necessary in early human development. The distinction made between man and woman in cultivation, education and treatment in childhood further contributed to the distinction in their social rank.

The changes that emerged in the century of light rested on new mainsprings. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá therefore did everything possible to throw more light on this subject during His travels in Europe and North America. He delivered to these people, as well as to the spiritual and political leaders of these regions, a clear vision of the need to bring their countries up to the new standard of an ever-evolving world. Despite the progress already achieved in these regions, He on numerous occasions raised the question of the equality between men and women, thus bringing to light the need for more to be done to make the substance of this equality a moral value and a well established belief for the entire population and a component of its identity.